Competence comes from experience, knowledge, skills, attitudes, values and beliefs. In the case of boards, which are the ultimate decision makers for most organisations, the competencies of directors are particularly important. Indeed, the Corporations Act 2001(Cth) requires every director to exercise reasonable care, diligence and skill in discharging their duties.

Further, for the third edition of the ASX Principles and Recommendations, the ASX Corporate Governance Council has modified the drafting of Principle 2 to recognise the need for boards to have an appropriate mix of skills, as well as an appropriate composition, size and commitment. The revised principle now also speaks in terms of boards discharging their duties “effectively” rather than “adequately”. Thus, Principle 2 in the third edition reads:

Structure the board to add value: A listed entity should have a board of an appropriate size, composition, skills and commitment to enable it to discharge its duties effectively.

But, what skills does a director need to be effective? How do you know if the spread of talent on the board reflects your organisation’s needs? Do all board members bring valuable skills, experience and expertise to the board? There is no simple answer to these questions. It depends on factors such as the organisation’s industry, the regulatory environment, the business model, and the capabilities of the CEO and management team. But while there is no easy answer to such questions, they are increasingly being asked.

Directors are required to perform a range of complex tasks and will often come from a range of different backgrounds that may or may not equip them with the skills to perform these tasks. Therefore, what is important for a board is that it has a good understanding of what skills it has and those skills requires. In doing so, it should take a strategic perspective. This will enable the board to adapt to the organisation’s current and future environment. For example, the boards of growing organisations preparing for an IPO will face evolving expectations and often require access to new skills.

The key benefits from a board skills analysis include:

- Identifying gaps in skills and diversity;

- Highlighting the strengths around the boardroom table to enable the directors’ skills to be utilised to their fullest potential;

- Identifying potential professional development opportunities for board members; and

- Informing the recruitment process for future board members.

Board skills analysis can also be effective in cases where replacing the current membership is not an option. Where such a board finds it is lacking in essential competencies—while not an ideal solution—the slack may be taken up by a highly competent management team or by external advisors and consultants. That the board has knowledge of its deficiencies and addresses these gaps in some form or another will go a long way towards individual board members demonstrating the care, skill and diligence expected of a director.

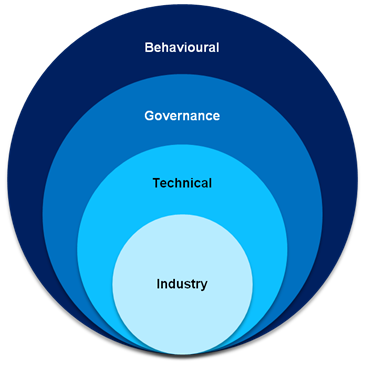

The figure below illustrates the four levels of competence required on a board.

Source: Kiel, Nicholson, Tunny & Beck, 2012, Directors at Work: A Practical Guide for Boards, Thomson Reuters, Sydney

The four areas to consider in director competence are:

- Industry: Experience in and knowledge of the industry in which the organisation operates.

- Technical: Technical/professional skills and specialist knowledge to assist with ongoing aspects of the board’s role.

- Governance: The essential governance knowledge and understanding all directors should possess or develop if they are to be effective board members. Includes some specific technical competencies as applied at board level.

- Behavioural: The attributes and competencies enabling individual board members to use their knowledge and skills to function well as team members and to interact with key stakeholders.

These four levels of competence can be divided into two categories. The first of these consists of the competencies that are required to perform the job efficiently (the directors’ industry, technical and governance competencies); the second relates to the kind of personal qualities that make for first class directors and effective boards. Sometimes it may be necessary to recruit directors with particular stakeholder contacts such as with governments and key suppliers. In general, however, there are certain industry, technical and governance competencies that are important to all boards. First of all, directors must be familiar with their individual duties and responsibilities as directors of the organisation. Next, it is also helpful if there are directors with industry experience through a detailed knowledge of the company or the sector in which it operates, as well as those who understand the broader industry environment. For example, it is often seen as advantageous to have one or more directors who have been or are CEOs in other organisations, as these individuals bring with them their own unique understanding and perspectives developed as CEOs.

Directors must all be aware of, and comply with, legal, ethical, fiduciary and financial responsibilities. On a practical level, this means being able to understand company balance sheets, profit and loss accounts, sources and methods of funding, cash flow and other financial data. In particular, following the Centro decision (ASIC v Healy (2011) 196 FCR 291; [2011] FCA 717), ideally all directors should be financially literate—that is, they have the capacity to scrutinise the content of their organisation’s accounts to ensure accuracy. It also means knowing the legal responsibilities of directors. These include familiarity with company law, contract law, and competition and consumer law, as well as the relevant industry and company codes of practice. Clearly, individuals will possess a greater degree of expertise in some areas than others, but breadth of experience and the preparedness to develop it further are the key requirements for any director.

In some organisations, the technical expertise a board member brings may not be regularly available to the management team and can be invaluable. Such specialist knowledge may outweigh any lack of governance knowledge on the part of the director—that is up to the individual board. What is important is that the board has an understanding of what competencies each director contributes to the board as a whole. This can be accomplished through a formal board skills analysis.

Each board or nomination committee will need to decide what competencies it wants in a director when developing a list of desirable competencies. This list can then be used in a skills matrix to assess the board’s capability requirements against the mix of current directors.

Based on our experience in conducting numerous board skills analyses, we believe a skills analysis framework should consider:

- the competencies and skills considered necessary for the board as a whole to possess to fulfil its role and in light of the organisation’s strategic direction;

- the competencies and skills the board considers each existing director to possess; and

- based on any gaps identified, the competencies and skills each new candidate should bring to the boardroom.

It should be noted that for each of the chosen competencies, there should be stages of development to describe performance in each skill (e.g. none to expert) with a brief description of performance at each of the stages. We find that to be effective the analysis must include a description of the skill and graduated indicators that identify the degree to which an individual has exhibited the skill or met the criteria, e.g. education level, number of years in a position, etc. Research has shown that a carefully developed criterion-referenced rating scale for competency assessment can be more reliable and valid than the simple skills analysis often used for boards, which lists a number of skills and asks for a rating (e.g. 1-5).

In summary, many boards either lack competent members or underutilise the competencies of skilled directors. The board must know what competencies it does, or does not have, if it wishes to move to the next level of effectiveness. To do so, board skills analysis may be the answer you are looking for.